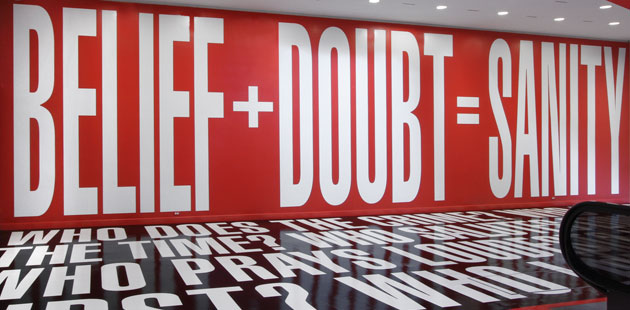

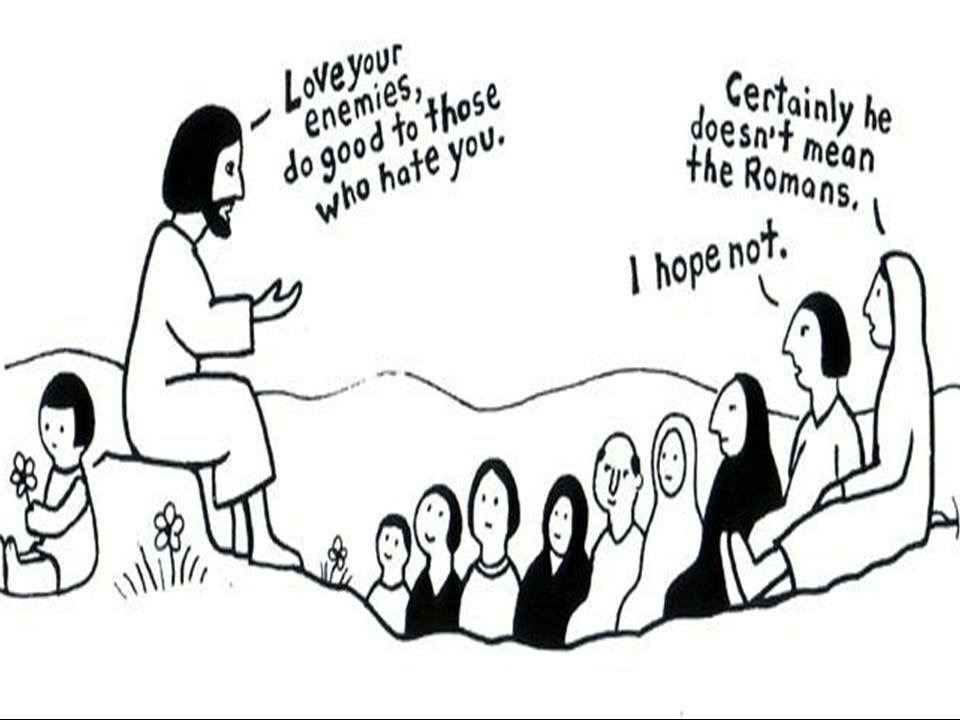

Based on a recent stake conference talk by a visiting area authority and subsequent comments I've overheard, Elder Ballard's General Conference message to "stay in the boat" seems to have become quite the catchphrase. Elder Ballard includes the solid admonition to "keep our focus on the Lord," but the title "

Stay in the Boat and Hold On!" ensures this will be what's most remembered.

Keeping with the water metaphor, Brigham Young is then quoted as likening the Church to a ship carrying passengers across the ocean--"the Old Ship Zion". Elder Ballard then asks the following: "Given the challenges we all face today, how do we stay on the Old Ship Zion?" For the vast majority of church members, staying in the boat is a lovely experience and the question of

how to stay isn't much of a concern. But there is a significant group of passengers experiencing seasickness for whom this question of

how to stay is a lot more poignant (maybe even painful) than Elder Ballard probably imagined.

The honest truth is that for seasick Mormons, "stay[ing] in the boat" is often made more difficult from fellow passengers within the ship--sometimes even from the crew. Desiring more diversity and living authentically with nuanced views can lead to frustrating encounters and even judgement from church family and friends who are generally satisfied with the way things are. If one is not content with the status quo, many assume something is wrong with the one. At times it feels as though the one must develop superhuman love and patience to continue in the boat healthily, or at least to avoid hitting someone over the head with an oar. When seasick, it's natural to question if we'd be better off

not being in the boat, or at least to question why staying in has to be so hard.

To those who are already hurting or seasick, the exhortation to "stay in the boat" isn't likely to be the most helpful message. The weather and conditions

outside the boat often look quite lovely in comparison to the conditions endured

onboard. A rare but unfortunate reality is that some prideful passengers attempt to throw others overboard whom they have judged to be unfit for the "Old Ship Zion". I use the word prideful deliberately because there's a certain degree of pride among passengers who take it upon themselves to pharisaically remind others of the ships rules and culture and care more about the boat itself than the condition of the passengers in the boat.

In her book

What a Friend We Have in Jesus, Chieko N. Okazaki (former counselor in the Relief Society General Presidency) wrote:

There is in an older edition of our LDS hymnal a warning to those who assume ‘all is well in Zion.’ It is a hymn we don’t sing anymore, but perhaps we should. It is entitled ‘Think Not When You Gather to Zion,’ and it reads in part:

Think not when you gather to Zion,

That all will be holy and pure;

That fraud and deception are banished,

And confidence wholly secure.

No, no, for the Lord our Redeemer

Has said that the tares with the wheat

Must grow ‘til the great day of burning

Shall render the harvest complete.

...Ed and I understood why it was hard for people to look past our skin color and slanted eyes to our smiles and our hearts. We heard many hurtful things. We had to deal with the fact that we couldn’t get car insurance or buy a home and that even at church, people hesitated to approach us. Ed and I said many times to each other, ‘If we were going to lose our testimonies, it would be right here in the heart of Zion.’

...And that’s perhaps why we loved this hymn, ‘What a Friend We Have in Jesus,’ and heard its echoes every time we sang ‘Israel, Israel, God Is Calling’ [the two have the same tune].

What a friend we have in Jesus,

All our sins and griefs to bear!

What a privilege to carry

Everything to God in prayer!

Do thy friends despise, forsake thee?

Take it to the Lord in prayer.

In His arms He’ll take and shield thee,

Thou wilt find a solace there.

The point is that just being on the "Old Ship Zion" doesn't guarantee all is well in Zion. And if all we do is constantly reassure ourselves of how wonderful and "true" the ship is, we too easily become complacent and forget that we each have a responsibility to make things

better in Zion. Perhaps we'll even forget our covenant to mourn with those who mourn and comfort seasick passengers needing comfort. We all would do well to become better acquainted with Jesus, the Master Healer, or as Elder Ballard put it, to "keep our focus on the Lord."

When we start focussing on other things, I start getting seasick.

In my Mormon experience, too often the focus has been on the Lord's church, even more than on the Lord. It seems to have become commonplace at church to speak of the church as though the church were the actual "good news". The gospel is the "good news." Church and gospel are not synonyms. We gather together because of the gospel--not for the sake of the gathering itself. If the gathering is only focused on itself, it's missing the life-giving gospel that brought us there in the first place.

When month after month after month people continue to speak and testify of "the church" as though it were the actual "gospel", you

know we have a problem with our focus. Overemphasizing the church while at church (

more than the actual gospel of Jesus Christ) is like being mesmerized so much by bathwater that people forget there's an actual baby in the bath. Even worse, if we keep our sights solely on the condition of the boat, we

all run the risk of loosing sight of the One who calms the waves and walks on water.

Elder Ballard likens church leaders to "experienced guides" of a river rafting trip, no doubt intended to instill confidence. This would be benign enough if only Mormon culture didn't presently have a such a problem with hero worship and

turning our prophet-leaders into idols. I wish I could minimize the degree of this crisis, but too often the grass-roots take-away message is that listening to the guides is naturally the same thing as listening to the One who created the water--or in other words, that trusting in ecclesiastical leaders is the

same thing as trusting in God.

This is idolatry, and it too makes me seasick.

Joseph Smith once said the people were

depending too much on the prophet and "hence were darkened in their minds". Notwithstanding, before long

emphasis/focus began to be placed on following the mortal church leaders even more than on following the perfect Savior. Maybe there's a healthy and mindful balance, but I'm pretty sure we're out of balance when it's

assumed that by following certain mortals in certain church callings we're

automatically following Christ. Autopilot substitution of the former for the latter creates an idol, and

some Latter-day Saints turn our prophets into idols without even realizing it. Is it any wonder some of us are getting nauseous? The scriptures warn about trusting in "the arm of the flesh," yet

how many

equate "trusting LDS priesthood authority" with "trusting God?"

I can trust that God is perfect, but my trust in prophets is different. I can trust the prophet to have inspiration

when acting as a prophet, and I can trust that prophets are doing the best they can in their unique stewardship and have our best interests at heart. But I'm not trusting them to be infallible. The pseudo-doctrine that prophets "

can't lead us astray" exists in tension with their expressed fallibility and leads some to mistakenly believe that prophets are perfect in the administration of the things of God. I get seasick when we oversell

expectations for prophets, even to the point that some Mormons forget that it's not the

(false) fourteen fundamentals of following the prophet that constitute the

fundamental principles of our religion, but rather the atonement of Christ.

This isn't to say that I don't respect the crew. They have a unique job and it's not an easy one. I love and

sustain them. But I'm not on board

because of the crew. Moreover, if the fundamental principle of our religion is the atonement of Jesus Christ, then it's definitely not fundamental that I agree with or even like everything coming from the crew, regardless of how many times I

'm told they won't lead the boat "astray". It puzzles me how often that word is used, and yet I'm not convinced we're all on the same page as to what

"astray" is even supposed to mean. Some assume this is a "promise" that the ship will never be guided wrong, and some assume it was the Lord who made such a "promise" in the first place. It's clear that we need to work through some tensions that inevitably come from

living with fallibility.

My understanding is that

the Lord chooses human beings to steer the ship, leaving to them their personality, humanity, talents, and weaknesses (see both

D&C 1:24 and

D&C 124:1.) The Lord has set the destination but gives the keys of the ship to mortals and grants them their agency to steer the ship to the best of their ability and with the faith that we'll reach our ultimate destination. I believe

we should support the crew as best we can--after all we're all in the same boat, and no one wants it to fail. But everyone--prophets included--works out their own personal itineraries with a unique blend of perspiration and inspiration, and sometimes mistakes are made--undeniably even big mistakes (such as

denying access to the temple and the priesthood because of race.)

As

President Uchtdorf put it: "I suppose the Church would be perfect only if it were run by perfect beings...but He works through us—His imperfect children—and imperfect people make mistakes." Why, then, do so many Mormons (including leaders) seem to want us to ignore that the ship is imperfect? Why insist our "guides" will never cause us any "

sad experience", despite what

D&C 121:39 says?

I don't expect infallibility from the crew anymore than I expect infallibility from the Old Ship Zion. Once upon a time there were some authorities who wanted their passengers to take comfort in the "fact" that the Titanic was "unsinkable." Knowing from sad experience how history played out--that it too proved to be fallible--prevents me from taking much comfort in even the most well-intended assurances from our authorities.

I personally don't need a perfect boat to stay afloat, so I'm not expecting a perfect boat ride. I know I'm not perfect so I don't expect perfection from anyone else. Maybe it's true that God will not let this particular ship crash into an iceberg and go completely under--maybe he would replace the captain before that happened. But based on past travel history, it's apparent to me that "

not being led astray" does NOT mean the guides can't take confusing detours or chart a longer than necessary route that delays our progress. Perhaps the guides will attempt to navigate a particular wave that makes me want to throw up. The ship may spend more time in shallow waters than I'd personally prefer, or get uncomfortably close to the cliffs. I may yet feel like strapping on a life-preserver and heading for the lifeboats. The ship's destination may very well be guaranteed, but there's no guarantee that I will always enjoy the ride.